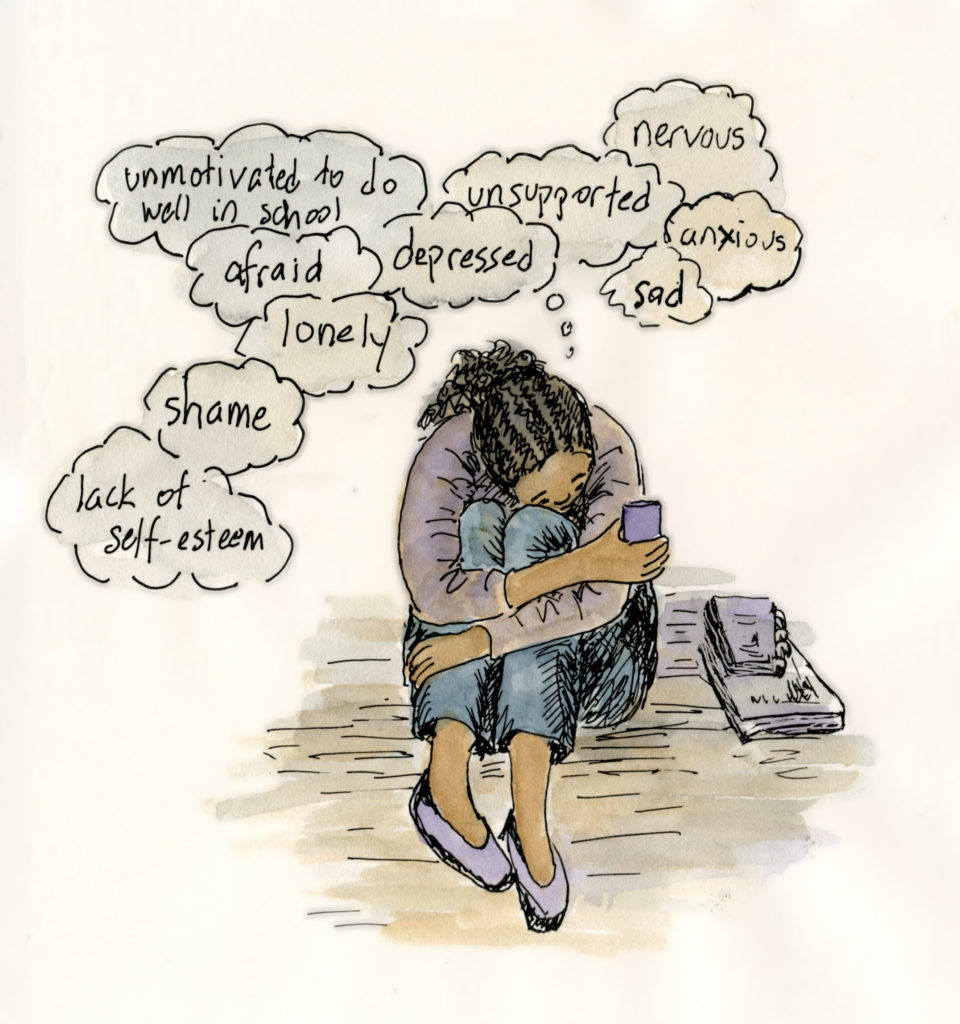

Public attention to cyberbullying has been rapidly increasing over the past decade due to numerous high-profile media cases, added attention by elected officials, and the wider availability of electronic devices and social media applications. This has posed the question as to whether cyberbullying should be considered worse than face-to-face, or traditional, bullying experiences. Research examining cyberbullying is relatively new. Therefore, we should start with what we know so far. While cyberbullying represents a major concern for young people, it is not a problem shared by all youth. In fact, cyberbullying is typically reported by middle and high school youth as happening less often than bullying done in-person. In addition, cyberbullying shouldn’t be considered a new behavior. It’s an old behavior wrapped in a new package.  We see cyberbullying connected to many of the same mental health difficulties that have been found by studies of traditional bullying, such as low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and social difficulties.

We see cyberbullying connected to many of the same mental health difficulties that have been found by studies of traditional bullying, such as low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and social difficulties.

However, while the field is still relatively young, we have seen that there are many factors that make cyberbullying quite unique. There are added concerns that individuals who cyberbully others can be anonymous and can potentially reach someone 24/7. There is also research to suggest that victimized youth tend to evaluate their well-being as worse when experiencing cyberbullying, even after accounting for their traditional bullying experiences. All of this suggests that while cyberbullying may be similar to bullying done in-person, both traditional and cyberbullying experiences are important to consider when thinking about mental health concerns. Several studies have now found that there is a considerable overlap in bullying experiences, with many young people reporting online and in-person victimizations at the same time. Our own study found that 77% of cyberbullied youth and young adults reported co-occurring traditional bullying. This raises the question: how do overlapping bullying experiences impact a person’s well-being? While studies on this question are limited, it seems that those who experience multiple forms of bullying have significantly worse outcomes than those who experience only one form. Therefore, it is important that parents, educators, and mental health clinicians alike refrain from attempting to label one type of bullying as the “worst,” and instead should consider the independent experiences of youth who experience single or multiple forms of bullying.

Research efforts must go beyond proving that bullying is a negative experience and must continue to consider what can be done to stop it. Several intervention and prevention programs have been found to be effective in reducing bullying behaviors, as well as promoting important skills that help all students grow, such as social and emotional learning programs. It may be more helpful for school staff to first focus on reducing traditional bullying, given that in-person victimization, when compared to cyberbullying, typically occurs more often and in younger youth. In addition, some research has suggested that programs that work in stopping traditional bullying help to reduce cyberbullying as well.

It is also important that we consider how to assist those who are bullied. One positive aspect of bullying research is that decades of studies show that not all youth who are bullied develop depression or other adjustment difficulties. In fact, the impact that victims of bullying receive depends on a number of factors. One important factor in promoting the well-being of victimized youth is helpful coping strategies. While many coping strategies, such as problem-solving, emotion regulation skills, positive thinking, and seeking support from others can be helpful for dealing with stress, research on coping with bullying has questioned how helpful these strategies can be for victims. This may suggest that some coping strategies typically assumed to be helpful do not help youth who are bullied. It also means that victims may need additional help to use these strategies effectively. For example, dealing with constant bullying can result in people feeling powerless and with limited control to change their lives. Therefore, engaging in typically helpful strategies, such as positive thinking and problem-solving, may be difficult and considered pointless. In addition, seeking out support from peers and adults is often identified as a helpful solution, but many who are cyberbullied tell us that they do not share these experiences with others for a number of reasons, such as a belief that adults will not understand their experiences or fear that they will have their cell phones, iPads, or computers taken away. Making recommendations to youth to stand up to bullies, deal with their emotions, and talk through their problems is an important first step. However, if youth who are bullied feel that they have little control or power to change the situation, as well as few friends or family who will understand their problem, they will not use these recommended strategies, but instead might engage in strategies that have been shown in research to increase their chances for more victimization and mental health concerns (e.g., avoiding, hiding their feelings, retaliating). Therefore, it is important that adults continue to model and help foster helpful coping and problem-solving skills for victimized individuals.

It is also important that we consider how to assist those who are bullied. One positive aspect of bullying research is that decades of studies show that not all youth who are bullied develop depression or other adjustment difficulties. In fact, the impact that victims of bullying receive depends on a number of factors. One important factor in promoting the well-being of victimized youth is helpful coping strategies. While many coping strategies, such as problem-solving, emotion regulation skills, positive thinking, and seeking support from others can be helpful for dealing with stress, research on coping with bullying has questioned how helpful these strategies can be for victims. This may suggest that some coping strategies typically assumed to be helpful do not help youth who are bullied. It also means that victims may need additional help to use these strategies effectively. For example, dealing with constant bullying can result in people feeling powerless and with limited control to change their lives. Therefore, engaging in typically helpful strategies, such as positive thinking and problem-solving, may be difficult and considered pointless. In addition, seeking out support from peers and adults is often identified as a helpful solution, but many who are cyberbullied tell us that they do not share these experiences with others for a number of reasons, such as a belief that adults will not understand their experiences or fear that they will have their cell phones, iPads, or computers taken away. Making recommendations to youth to stand up to bullies, deal with their emotions, and talk through their problems is an important first step. However, if youth who are bullied feel that they have little control or power to change the situation, as well as few friends or family who will understand their problem, they will not use these recommended strategies, but instead might engage in strategies that have been shown in research to increase their chances for more victimization and mental health concerns (e.g., avoiding, hiding their feelings, retaliating). Therefore, it is important that adults continue to model and help foster helpful coping and problem-solving skills for victimized individuals.

How to help children who have been bullied:

- Be aware of the site and applications that your children are using. Be familiar with the purpose of the site and the typical content that is shared. Youth who are cyberbullied often report little interest in sharing their experience with their parents. While there are many reasons for this, one reason that has been reported by youth is the belief that adults do not understand the technology or social media sites that they use. These youth then question how helpful adults can be for addressing cyberbullying, given their limited expertise with technology. Therefore, it is important that parents know and understand the sites and applications being used by their children. Parents should have conversations with their children prior to allowing them to use social media about their expectations and the need to share their online experience with adults. Parents should also regularly check-in on their child’s online experiences, encouraging discussion about what applications they use and their experiences while using them.

Encourage your child to share difficult social problems, such as bullying, with you. Parents should listen to their children’s experiences and help them to consider their options for addressing the problem. All too often, our first response is to compare our children’s bullying experiences to our own or to offer suggestions for how to solve the problem. Although adults mean to share these responses as a way to connect and support, they can often come across as minimizing the experiences of the child. Therefore, when in doubt, listen. Be present. In addition, do not simply offer solutions that your child has likely already considered (and may feel they are unable to use). Instead, help model and practice appropriate problem-solving by encouraging children to think through their options. It is likely that many helpful (e.g., talk to a teacher, assertive response to the bully) and unhelpful (e.g., fight the child, never return to school) may be considered. Instead of telling youth which strategies are best, help them to consider the consequences of their actions and to use this information to select the best response(s). Assisting your children in solving peer conflict can help develop better problem-solving skills, as well as to foster a belief in victims that they are not helpless and can do something proactive about bullying.

Encourage your child to share difficult social problems, such as bullying, with you. Parents should listen to their children’s experiences and help them to consider their options for addressing the problem. All too often, our first response is to compare our children’s bullying experiences to our own or to offer suggestions for how to solve the problem. Although adults mean to share these responses as a way to connect and support, they can often come across as minimizing the experiences of the child. Therefore, when in doubt, listen. Be present. In addition, do not simply offer solutions that your child has likely already considered (and may feel they are unable to use). Instead, help model and practice appropriate problem-solving by encouraging children to think through their options. It is likely that many helpful (e.g., talk to a teacher, assertive response to the bully) and unhelpful (e.g., fight the child, never return to school) may be considered. Instead of telling youth which strategies are best, help them to consider the consequences of their actions and to use this information to select the best response(s). Assisting your children in solving peer conflict can help develop better problem-solving skills, as well as to foster a belief in victims that they are not helpless and can do something proactive about bullying.

- Advocate for your child with school officials. Students may not feel that they can share their bullying experiences, particularly cyberbullying, with school officials or believe that anything will be done to stop the bullying. Therefore, it is important that parents advocate for their children and discuss these concerns with school staff, but only after first discussing options with their children. Research on social support for bullying often suggests that support can be a helpful tool. However, the findings have been mixed. Some research has suggested that too much support from others may not help victimized youth. Other studies have shown differences in the helpfulness of support by age and gender identity. For example, it has been suggested that males often seek less support from others and may experience social difficulties when using support for bullying concerns (e.g., less social acceptance). Therefore, it is important that adults discuss with youth how they might best support them when victimization occurs. Youth who hope to be supported emotionally and instead have their parents visit their school officials may be left feeling embarrassed and questioning if they should share these experiences with their family in the future. Supporting children who are bullied is an important way to possibility mitigate some of the mental health concerns associated with bullying. Discussing the type of support with your child should be the first step.

- Seek out therapeutic support. Given the decades of research linking bullying victimization to mental health concerns, bullied youth may benefit from therapeutic support, such as working with mental health professionals within their school (e.g., school psychologists, school counselors, school social workers) or clinicians within the community (e.g., community-based mental health centers, private practice). Cognitive-behavioral therapy may be particularly suited for addressing the potential cognitive (e.g., negative self-thoughts, thinking errors), behavioral (e.g., social withdrawal, school refusal), and specific mental health concerns (e.g., depression, anxiety) associated with being bullied. Childhood and adolescence represent an important developmental period marked with increasing demands on social and behavioral skills, as well as an elevated risk for experiencing significant stress and developing various psychological disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression, ADHD). While bullying represents just one of many important social stressors that youth may face, parents and educators should monitor the mood of victimized youth and consider therapeutic supports when necessary.

For more information:

We want to thank our special guest blogger, Mr. Zachary Myers. Zach is a doctoral candidate in the School Psychology Program at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He is currently completing his doctoral internship at the Boys Town Center for Behavioral Health in Omaha, Nebraska. His research interests include the relationship between multiple forms of bullying victimization (e.g., traditional and cyberbullying) and mental health concerns, as well as how victimized youth cope with their bullying experiences.

We also want to thank Dr. Sue Swearer, Zach’s doctoral/academic supervisor, for her insight and support. Dr. Swearer serves as the Willa Cather Professor of School Psychology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and co-director of the Bullying Research Network. As principal investigator of the Target Bullying: Best Practices in Bullying Prevention and Intervention project, Dr. Swearer has a long-standing track record of working with schools and districts nationwide to help reduce bullying behaviors. She partnered with the Making Caring Common Project at Harvard University and Career Training Concepts to develop the HEAR presentation.

To learn more about the work of Dr. Swearer, visit empowerment.unl.edu. Also, connect with her on social media: Twitter (@DrSusanSwearer, @Bully_Research) and Facebook via the Empowerment Initiative and Bullying Research Network pages.

For more information about HEAR, please contact Dr. Amy Smith by phone at 678-405-5670 or by email at [email protected].